Author’s note: Have you had a PD day recently, or have one coming up in the next couple of weeks? This post has been written to help educators, school leaders and district leaders reflect upon the observable impact of their professional learning and to provide tools to help them plan for impactful professional learning in their context. Ask yourself a question: what is that you do AFTER a professional development day to ensure an impactful professional learning experience for the educators in your school? When we have asked this question of district leaders, school leaders and instructional coaches across North America the answers are quite varied. Responses tend to range from exit tickets, to checking in with teachers the following week to see how the day was received, to asking collaborative teams what next steps might look like, to having a staff members share their takeaways and how they might implement some of the strategies that they saw in their classrooms with their students. Some school and district leaders also confess that because of the size of their schools and districts, it is a big enough challenge just to coordinate the actual professional learning day: in terms of what is done after PD days, there are just too many people to keep track of. Now ask yourself another question: what is that you do BEFORE a professional development day to ensure that it will be an impactful professional learning experience for the educators in your school? Too often, the answer (beyond arranging speakers, venues, agendas, food and parking) is ‘not as much as we should’. And now one final question: what was the OBSERVABLE IMPACT of the last professional development day that you had in your school or district? (In the Observable Impact model, we define observable impact as ‘observable changes in classroom practice that lead to positive outcomes for students’). This is not a condemnation of professional learning days, nor the hard-working educators and support staff that coordinate professional learning or the educators who dutifully participate in professional learning sessions throughout the school year. Well-meaning school leaders spend thousands of dollars bringing in polished professional developers to deliver compelling keynote speeches that are directly aligned to where their schools want to go. We send educators to workshops to learn about the importance of critical thinking, creativity and innovative teaching practices to align with the 21st century skill pieces that make up their Vision of a Learner. But the activities of the day often look like the audience sitting back and listening, laughing at the jokes, watching compelling video clips, scribbling down a few notes, and clapping loudly at the end while extolling the virtues of the presenter. Yet at the end of sessions such as these, the information doesn’t always "travel well", or turns into what we might call “Snapchat” PD. While we might leave a conference feeling more energized, empowered and ready to transform learning when we get back to our schools, much of the momentum gained from aspirational professional learning seems to either get lost on the plane ride home or lost in translation to their classes. Too often, there is little tangible proof that the presentation caused positive changes to teacher practice and student learning. Instead we say things such as, “Remember when we went to San Diego?” and recall when a colleague lost their luggage, and an interesting catch-phrase or two that we heard. While at some point in the past it might have been acceptable for us to say, “If I get ONE thing out of the PD day that I can use in my classroom, it’s been a great day,” getting one thing out of a full day of learning is no longer (and never really was) acceptable as a good return on the investment of attention, energy, time and resources of our teachers. It is important to point out that the PLC 2.0 model is not designed to tell teachers or school leaders which professional learning they need to do in their schools, nor whether one conference is better than another. While judging whether professional learning as ‘good’ or ‘bad’ is commonplace, it serves little purpose unless it is directly related to the most important piece of the PLCPLC 2.0 model: OBSERVABLE IMPACT. The question we should be asking ourselves when planning professional development is “Will this professional learning have observable impact?” If we want to have professional learning that is impactful, we have to PLAN for impact. Recently, while working with a group of teachers from the midwestern United States, we asked them to recall their most impactful professional learning experience and to describe some of the elements of the experience that they felt made it so impactful. It was not surprising to hear them say:

Their responses are not dissimilar to what research would tell us. Seymour Sarason (2007) said, “Sustained and productive contexts of learning cannot exist for students if they do not simultaneously exist for teachers.” In Effective Teacher Professional Development (2017), Darling-Hammond, Hyler and Gardner suggest that effective professional learning is content-focused, incorporates active learning, supports collaboration, uses models of effective practice, provides coaching and expert support, offers feedback and reflection, and is of sustained duration. In the PLC 2.0 model, we believe that professional learning must engage educators through each of three lenses:

Whether we are considering staff meetings, collaborative time, inservice or professional development, our time for professional learning is precious. Planning for the observable impact of professional learning helps us to ensure that the resources and energy are worth our investment. An example to consider: Imagine that you were a newer golfer, and you wanted to improve your game. What would be the most efficient and effective approach to getting better, especially given your busy schedule? Would you ask our friends that you play with every Sunday for some tips and hope that "the expertise was in the room"? Would you go to a golf course and book some lessons? Or would you examine your own game through your observations and perhaps the eyes of your peers, determine that putting on the green is your area of challenge, and research the best local golf instructor that you could and investigate their area of expertise, their cost, and their approach to golf instruction to ensure that their methodology was likely to be effective for you? Now substitute an essential attribute for our students from our vision for the learners in our school, something like “creative thinking”. If we substitute “golf” for “creative thinking”, as in the example above, we would likely note that sometimes the expertise is in the room, and sometimes it is NOT in the room. All of us would agree with this when it comes to golf, and it is equally feasible to say this when it comes to an area such as the effective instruction of creative thinking in intermediate language arts. When we are struggling with something with our students, it’s ok for us to be vulnerable enough to say we need some external expertise and research to move us in a promising direction--we need some help! In truth, if we already knew exactly what to do, we would likely already be doing it. Not knowing the next course of action doesn’t mean that we cannot speak to other collaborative teams within our building or in neighbouring schools or districts. Nor does it mean that we cannot look at what the research says about a particular approach that seems to have some promise. In the PLC 2.0 model, we want to avoid the "let’s just go get some professional development" approach and chase after the next flavor-of-the-month. We believe that resources are scarce and time is precious; the more specificity in the understanding of our learning challenge, our supporting evidence, and research around promising practices, the more likely we are to create our most informed theory about the professional learning that moves us closer to our vision. In The Practice of Adaptive Leadership (2009), Ronald Heifetz et al. state: "When you view leadership as an experiment, you free yourself to see any change initiative as an educated guess, something that you have decided to try but that does not require you to put an immovable stake in the ground. Your intervention is evidence of your commitment to your purposes, but it is not your final word on how to get from here to there." The reality is that our schools, the people that work within them and the communities we serve are complex systems and not everything that "works" actually works. Ryan Fuller said it best when he said, “Teaching is not rocket science. It’s harder!” As a result, when it comes to professional learning, we are really creating a hypothesis for impact that represents our most promising "educated guess," as Heifetz indicates. When we create this hypothesis, we can begin to determine the actions that get us closer to our Vision of a Learner. In the PLC 2.0 model, we call this hypothesis our Action Statement, which we create using a stem of “If we do … then we will observe …” For example, consider a sixth grade math team team who wanted to improve students’ ability to think creatively in order to come up with multiple means to solve word problems. Their Action Statement might look something like this: If we attend the full-day workshop on "math talks" for intermediate math, then we will observe …

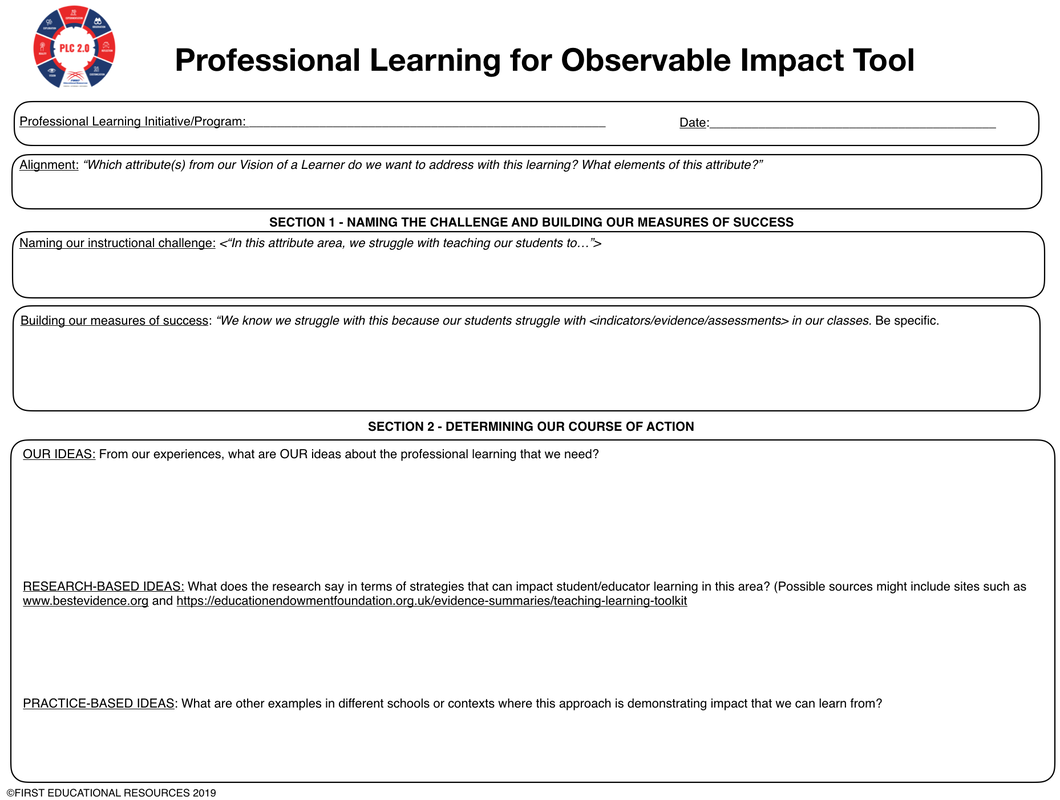

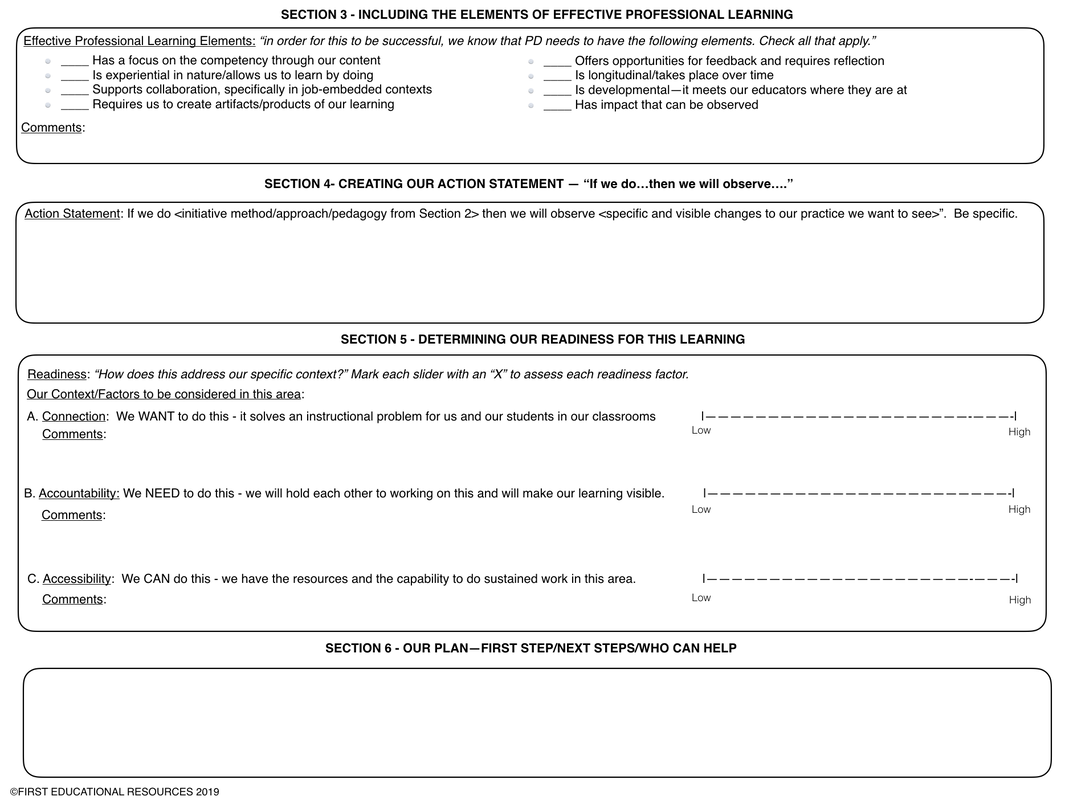

By being explicit about the products of our learning that we want to see before we begin a cycle of professional learning, (a) we can assess potential professional learning pathways before we actually embark on the journey rather than go charging down the wrong direction, and (b) after the professional learning is complete, we can look back and determine whether that professional learning was successful in meeting some or all of the look fors that we had determined. Imagine presenting your Action Statement to an external expert on creative thinking prior to hiring them and asking them how best they would be able to support your vision of the learning that you have detailed. Not only would this be helpful for your school, but it also helps an external expert customize the learning experience for your school context. By planning for impactful professional development, not only will an Action Statement make our educated guess on professional learning significantly more educated, it will allow us to look back and answer the question that is central to PLC 2.0, “Did our professional learning have observable impact?” Try the Professional Learning For Impact Tool (see below) in the PLC 2.0 Toolkit--it can help you and your collaborative team co-create your plan for your next professional learning and connect that professional learning to impact where it matters the most--in our classrooms with students and teachers.

0 Comments

“What is the OBSERVABLE impact of your PLC time?” Ask yourself this question--as a school leader, as a teacher. In fact, ask your students this question! If you are like one of the thousands of schools across North America and around the world who has went through the process of gaining consensus from educators and approvals from parents, district officials and board members to create embedded time within the school day for educators to collaborate over the last several years, one a scale of one to five (five being highly impactful), how might you rate the impact of your collaborative time? It’s an interesting question, and from our experiences working with schools across North America (and my own experience as a former high school principal of a model PLC school) the responses to this question on from teachers have largely been in the ‘twos’ and ‘threes’ on the five scale, depending on whether their school or district leaders were in the room. However, when we ask educators the same question using the PLC 2.0 definition of OBSERVABLE impact, which is ‘observable changes in teacher practice in the classroom as a result of collaboration that lead to improved student outcomes’, the self-assessment of their collaborative efforts by those very same educators tends to drop significantly. Despite the best intentions of our educators and their efforts with their peers and their students, we began to hear things during our PLC time from our collaborative teams such as:

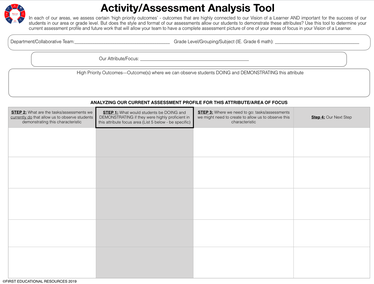

Do any of these sound familiar to you? If so, you would not be alone! In “Teachers Know Best: Teachers’ Views on Professional Development,” hundreds of teachers were asked, “Overall, how would you rate your satisfaction with the PD offered to teachers in your school district/school?” Of seven factors, including things such as courses, conferences, and coaching, participating in a professional learning community was rated the lowest in teacher satisfaction by a significant margin! The report went on to state, “Professional development formats strongly supported by district leadership and principals, such as professional learning communities and coaching, are currently not meeting teachers’ needs.” This does not mean that collaborative time is not important (if not essential!) to the process of improving our practices in the classroom to prepare students for life beyond the K-12 system: the research on teacher collaboration is clear. However, the PRACTICE of teachers collaborating has been much cloudier, and when it comes to impact, hard-working and busy educators are often left to wonder whether the return on their collaborative efforts has come out on the positive side of the ledger. This is why PLC 2.0 has been created--to help educators see the observable impact of their collaborative efforts. In PLC 2.0 Collaborating for Observable Impact and the PLC 2.0 Toolkit, educators will find tools and collaborative team protocols that make the precious collaborative time that we get to spend with our colleagues and community members as meaningful and impactful as possible. The tools (check out a sample of the ‘Activity/Assessment Analysis Tool’ and collaborative team protocol here) that have been created to be interactive, step-by-step ‘mini-workshops’ to make the products of collaboration time visible, and to make the process of collaboration varied and (gasp!) enjoyable! Being a teacher is hard work, and collaboration is not something we should dread—collaborative teams should look forward to working together on things that matter to their classrooms. Furthermore, many of the activities in the protocols are ones that teachers can easily adapt to use in their classrooms to make the products of student learning visible. Why shouldn’t we walk away from a collaborative meetings with things that we can actually use? In PLC 2.0, the measure of success for teacher collaboration is NOT to be a professional learning community--it’s OBSERVABLE IMPACT. The time we spend working together to improve practice needs to lead to visible changes in what students and teachers are doing and demonstrating and the types of activities and assessments that take place in the classroom. Period. PLC 2.0 is a process that is designed to help educators create a vision of the learning that they want in their classrooms for their students and to then use tools and protocols to make that vision observable for all learners. PLC 2.0 helps teachers, school administrators and district leaders answer six guiding questions in THEIR context. These guiding questions of PLC 2.0 are:

A key message for PLC 2.0 is “Wherever you are is exactly where you need to be!”. The PLC 2.0 approach has multiple entry points. If your district has a vision of a learner--great! How can we make this vision observable in our students, our educators, and our activities and assessments. Your school already has a professional learning plan for the year to guide educator learning? Fantastic! Use the tools in the PLC 2.0 Toolkit to determine whether your professional learning is having the level of impact in the classroom that you and your team is hoping for. There is no wrong place to start in the PLC 2.0 model, because each district, school, department and teacher is at a different spot when it comes to making observable impact in the classroom. PLC 2.0 is all about connecting educator actions to the impact they have on students in the classroom so that teachers know that their collective actions make a difference to student learning. And we know that teachers believing that their collective efforts make a positive difference to student learning regardless of the students that they teach (AKA. collective teacher efficacy) has the highest effect size for student achievement of ANY factor that contributes to student success! As Jenni Donohoo, author and world thought leader on collective teacher efficacy said: “Collective efficacy is strengthened when teams see the result of their combined efforts, and they will do so by engaging in the PLC 2.0 process. PLC 2.0 is the impetus needed to collectively move PLCs to observable impact.” So if you would like to answer the question “What is the observable impact of our collaborative efforts?” and help connect your educators’ actions to impact in the classroom, check out PLC 2.0 - Collaborating for Observable Impact in Today’s Schools and the PLC 2.0 Toolkit. Action means "We did it!", but “impact” means "It mattered." Authored by: Cale Birk, PLC 2.0 Imagineer and Vice-President of FIRST Educational Resources *Purchase 10 copies of the PLC 2.0 Bundle for your school and receive all of the tools in interactive form via Fillable PDFs and Word Documents Have you ever been to a website and forgotten your password?

Fun, isn’t it? Those seven or eight minutes where you go to a website with vague recollections of a previous account and unsuccessfully try to log in. From there, the adventure begins--you try to create a new account (but of course it says that the email you have provided is linked to an existing account), ask for an email to be sent to that account, wait, open that email, copy that link into your browser along with a temporary password, and proceed to have to make a new password with 12 letters, numbers, capitals, and some Greek symbol which you are confident you will forget in the next two to three minutes. The best part is that you write the password on a post-it note and stick it to your monitor so it is easily accessible to the mischievous thieves who wish to steal your access to at 15% off coupon at Designer Shoe Warehouse. Groan. Whether it’s the resetting of a password, the pay parking kiosk that expects you to know to press the pound sign after entering your license plate number, or the new digital marks program that the IT department has set up for the school district that requires you to manually enter your class lists that are already loaded in the system, we all tend to ask the same question after gnashing our teeth in frustration: “Did the person who MADE this <enter your experience, product or service here> ever TEST this with the people who would be USING this?” When solutions are designed without a deep connection to the problem AND those who will actually experience solution, designers can cause dissatisfaction, frustration, resentment and anger--they can even cause circumvention of the entire process or service, and outright resistance! In the K-12 school system, it is common that, when school leaders are presented with a challenge in their school community, they want to design a solution to the problem...quickly! We often feel like the next problem is just a phone call or a knock on the office door away, so we better get through this one as fast as we can. We often don’t want to burden our busy colleagues with helping us solve the problem, and as a result, much like the old game show “Name That Tune” where guests tried to name a song in the fewest notes possible, we try to solve the problem as quickly as possible with minimal disruptions to the homeostasis of our learning environment. There are so many examples of this in our schools. Kids are starting to wear spaghetti straps and muscle shirts again as summer approaches? I’ll get a bigger posters with the dress code on it, and adorn them with a couple of cool school logos so kids will pay it more attention. We want teachers to collaborate? I watched ‘Field of Dreams’, so let’s adopt the mantra of “If we build it, they will come” and convert some instructional time into PLC time. Low attendance at Parent Teacher Interviews in the evening? Let’s change the time slots and put them in the middle of the day. As school leaders, we can likely think of countless times that we might have thought that we were ‘solving a problem’ (much like the designer of the password recovery protocol), only to be surprised to find our solution was met with that same dissatisfaction, frustration, resentment and anger. And resistance. As school leaders, very often WE create this resistance. Ouch. Hearing something like that likely doesn’t feel too great. Juggling endless improvement initiatives, shrinking budgets, growing societal demands, ramped up accountability and increasingly diverse learner needs is hard work to say the very least! So when we hear that WE might be the ones creating resistance to change or new ideas in our school communities, it can definitely sting. When we are working at top speed, likely the last thing we want to hear is that we might be alienating the very people we are trying to serve in the process. So how do we avoid creating resistance? We can start by re-thinking the word ‘resistance’. Imagine that tomorrow, someone told you that your school was going to be rebuilt: you and your school community were finally getting the upgrade that you had been dreaming about for the last eight years. A committee to develop the new design was going to be struck, and in the next two years, the new digs would be up and running. So exciting, hey? Except for one tiny little thing. As the school leader, you were not invited to be a part of the design committee. Hmm. You found this quite odd because you were going to be the one that was working and supervising the building! Not only that, you had good ideas, and you were really passionate about school design. However, you found out after through a colleague on the committee that you were excluded because a few people thought your ideas were “a bit too radical”, and you “were not always on board” with the way the school community had operated in the past. The committee thought they would be better served by having members that were “going in the same direction”: by having enough like-minded people, a critical mass would be developed that would push the final design through any resistance to the direction that the committee took. How would you feel? Would you feel connected to this project? “Too radical?” What the heck were they talking about? I just want to have projectors, sound, wifi, and flexible seating for our students and educators, you say! “Not always on board?” You were just expressing your opinion when you said that project-based learning is a better way to engage students than the worksheets and tests we were currently giving to students. You still thought foundational skills were important-- PBL is just a better way to learn the foundational skills AS WELL AS things we know kids will need, like critical thinking, creative thinking, and communication! Why can’t they see that? “I am not a resister, I just have a different opinion!” you might shout to no one in particular. So how might it feel to one of our passionate teachers who might have ideas that we thought were “a bit too radical” when we exclude them from a team to design a solution to a problem in our schools? How about that staff member who “isn’t always on board”, or “isn’t always going in the same direction”? Do we just automatically disqualify them in favor of that keen go-getter who is always up for anything? We all have those, don’t we? The thoroughbreds that we hitch our wagon to so we can tell the others to get on board or be left behind. Do we only surround ourselves with those who are like-minded in their thinking and most supportive to head in the direction that we wish to go? But here is a question to consider: if we exclude those with diverse opinions when we begin to really dig in to a problem, do we truly believe that we are going to get them to “buy-in” to a solution created by the thoroughbreds at a later date simply because the thoroughbreds are already doing it? Speaking from experience, and with more than a little regret for the times when I chose not to include those with diverse opinions who were not always on board, I can tell you it rarely works out. All I did was further alienate those individuals in the process. Ugh. Two years ago, at the Business Innovation Factory Summit in Providence, I had the good fortune to sit with Jamie Casap, the Global Educational Evangelist from Google. For a few minutes we spoke of the importance of diversity, and in his keynote to the participants later that day he reminded all of us that the diversity that we have in our schools and communities is truly our competitive advantage! So why not embrace the diversity of the people and opinions in order to help us understand the challenges AND the people experiencing those challenges in our schools so that we can come up with lasting and meaningful solutions for ALL of us while connecting to the group in the process? In Learner-Centered Design, re-thinking resistance is foundational to changing the learner experience in our schools. LCD places the experience of the learner at the forefront of our experience design--and not just for the learners we like or those that are ‘on board’. We design for all of our learners, even those who might be the most ‘diverse’ in their opinions. And in order to effectively design experiences for the diverse learners we serve, we must recognize that our diversity is our competitive advantage in changing the learning experience, much like Jamie Casap stated in Rhode Island. Our competitive advantage lies within our ‘resisters’. Our challenge is to re-think resistance.  Let me get right to it: I believe that we have to shift our thinking about the whole “leadership versus management” concept in K-12 leadership for our schools. More specifically, we need to think differently about what drives us to say: “I want to be an INSTRUCTIONAL LEADER, but all I get to do is MANAGE.” In your own context as a school leader--what are the things that you enjoy doing the most? If you are like most administrators, your answers are likely centred around activities with teaching and learning, such as visiting classrooms and working with teachers to design engaging classroom environments. You probably enjoy solving problems, collaborating with colleagues, learning new things and trying different ideas. And most of all, you like leading! You like helping to chart the course for the school and the learners within it, and to develop and implement the initiatives that will improve learning for all students. Unfortunately, the work of a school leader can often seem to bear little resemblance to the title itself. In 2013, the Alberta Teachers' Association and the Canadian Association of Principals conducted 40 focus groups with 500 principals from across Canada over the span of two years, and created a document called the "Future of the Principalship in Canada". In this document, school leaders reported that they spent less than 15% of their time doing leadership-related tasks! The bulk of their day was spent on internal administrative tasks, teaching or covering classes, meeting with students, parents, or external agencies, or responding to requests from their districts, the province or the Ministry of Education. When I was working with a group of administrators at a leadership retreat a few months ago, a Vice-Principal of a large high school summed up these findings when he proclaimed “I took this job to be an educational leader, and now I just put out fires. I have a Master’s Degree in locker assignments!”. And while the group laughed, the message was clear: Principals and Assistant Principals want to be leaders for their students, teachers, and school communities, yet the majority of their time is spent running, reacting and responding to the day-to-day operations and management of the school. And while I wish that I had better news to report, I don’t think that the tilted balance of management over leadership will ever change. In fact, I think it may actually get worse. But what if we flipped that whole concept on its head? What if we planned staff meeting activities that used the management tasks that we are required to ‘cover’ as the content to model the skills we want for our teachers and classrooms so we can be the instructional leaders we want to be? #saywhat? In British Columbia we are asking teachers to shift their approach to teaching and learning through the new BC Curriculum, and I could not be more excited. When I reflect upon my days as a teacher of Senior Biology, I remember looking with bewilderment at the hundreds of outcomes that I needed to cover for my students so they would be prepared for the government exams at the end of the semester. How was I going to get the kids through this stuff? And while I wish that it were different, I know there were too many lessons when I would tell my students something like “Sorry gang, this is going to be like drinking from a firehose today--we just need to get caught up!”. The kids would lock in, get their pens ready, and I would blast through as many outcomes as I could in the shortest period of time possible. My focus was content coverage: regardless of how much I would have liked to have been an instructional leader and taken more innovative and creative approaches, I felt like I was just barely managing the time it would take for me to get through the content of the course. Things like the 4 Cs’s of critical thinking, creativity, collaboration and communication--were distant afterthoughts behind “the number one C”-- CONTENT! The new BC curriculum is asking teachers to take an entirely different approach. Rather than just teaching content, teachers are being asked to teach the competencies of thinking, communication, and personal and social responsibility USING the content as the vehicle to get there. The content has become the means to help students learn to think critically and creatively, and communicate their learning as it relates to their own identity and their surroundings. As school leaders, we are asking teachers to move from a place where they have had to manage class time to cover content to now becoming instructional leaders who use their content to teach the competencies students will need to be successful in the future. In other words, we are asking teachers to use their content to teach skills. If we are asking teachers to be instructional leaders who use their content to teach skills, school leaders must do the same. It’s just different content. If we think for one minute that students find kinetic molecular theory in their science classes any more engaging than our teachers find covering the latest District policies in our faculty meetings, we are simply fooling ourselves. If we expect teachers to use kinetic molecular theory as an opportunity to teach communication and critical thinking to their learners in their classrooms, then we must hold ourselves to using policies and ‘administrivia’ as opportunities to teach OUR learners in OUR classrooms--our faculty meetings. If we expect this of teachers, we must expect this of ourselves: if we continue to say “I would like to lead, but I am too busy managing!”, then it would follow that our teachers should say “I would like to teach the competencies, but I am too busy covering content!”. We can’t do that anymore. Leaders don’t make excuses about why they are unable to lead. They just lead. The art of school leadership is not just about leading when we are ‘supposed’ to lead. It’s not just standing in front of the school at school assemblies, or in front of the parents at the Parent Advisory Council meetings, or introducing the guest speaker at PD days, it’s about relentlessly seeking out opportunities to model leadership, even when it is least expected. And it starts when we can take our managerial ‘content’ and turn it into instructional leadership. But how do we do this? Any educator knows that one of the keys to instructional success is planning. In my recent work with school leaders, I introduced them to an Experience Planning Template that was co-designed with Learning Experience Designers and Principals. Within this planning template, along with standard things like ‘learning intentions’, there are several other key pieces for leaders to consider, such as:

There is never enough time. But perhaps an alternative thought might be this: If a topic is important enough for us to have on our staff meeting agenda, should we not want to use it well? If these are so-called ‘management tasks’ that we must do, is our goal not for our teachers to be learners, not only about the managerial task, but about their practice as a teacher? And is it not incumbent upon the instructional leader to find the opportunities to lead, even when they could simply just ‘manage’? But from a more pragmatic perspective, here is another thought. As school leaders, we actively encourage our teachers to collaborate, to share effective lesson plans and share resources. “Why re-invent the wheel?” we say, “Make it easier on ourselves!”. So why don’t we share effective staff meeting lesson plans? Why is it so common for us to plan the staff meeting by ourselves the day before, or with our small leadership team on the Friday prior to the Monday of the meeting, working from a ‘collaborative agenda’ that a few staff members have contributed to with issues from around the school? This template was not only designed WITH Principals and Learning Experience Designers (who are teachers, of course), it was designed FOR Principals and their staff to co-design their learning. And it was designed using a collaborative document that will be shared in a repository for all of our administrators to access so people would not have to ‘re-invent the wheel’. Ask yourself this--how much time do you spend planning your current staff meetings? And with all of that planning, are there times when you feel like you are just ‘covering content’? For most of us, the answer would be ‘yes’. But if there were a way that you could use that content to be an instructional leader, would you choose to do that? And even better, if a school leader had already used that content (or similar content) to model competencies for their staff and was willing to share their ‘field-tested’ plan and reflections on how to make it better with you, would that be something that would help you be less of a ‘manager’ and more of a ‘leader’? Whether we like it or not, the minutia of day-to-day operations is something that school administrators must do. While we might hope, it would be naive to think that the ‘administrivia’ will change or diminish in the near future. But if we can take even some of these pieces and turn them into instructional leadership opportunities and share them with our colleagues, we can re-think the whole ‘leadership versus management’ dilemma. We can be leaders without excuses and just lead. Across North America, the first couple of weeks of school are complete. Students are settled into their classrooms, teachers have begun to dive into the curriculum for the year. As a former senior biology teacher, I remember looking at my curriculum guides and course outlines at the start of each year thinking the same thing--my students are once again going to struggle with understanding the process of gas exchange in respiratory system.

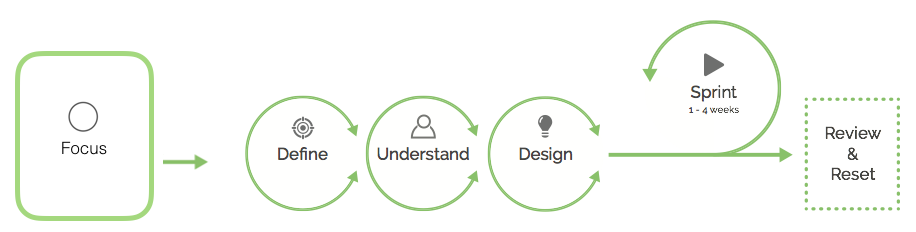

Sigh. It was never all of the students of course--some would pick up the concepts fairly quickly. But year in and year out, as fast as you could say ‘carbaminohemoglobin’, I knew I was going to have a core group of students that just wouldn’t get it. Does this resonate with you? Do you have an outcome in your course where you KNOW kids will struggle, even before you have started to teach them? Outcomes like number sense. Grammar. Fractions. Balancing chemical equations. Compound sentences. Hum a few bars if any of these tunes sound familiar to you, or sing your own song if you are thinking something more along the lines of conjugating verbs in a language class or proving trig identities in math. Those outcomes that, year in and year out, a few students always find to be challenging. Not only was I aware of this outcome, I also felt like I had tried every approach short of shrinking students down to the size of a red blood cell to get them to understand gas exchange! Yet it seemed like no matter what I did, no matter what year it was or which group came through the door, there was going to be a certain set of students that didn’t pick up what I was throwing down. Death, taxes, and five students who got lost when I taught gas exchange--those were certainties in my world. I couldn’t spend any more time de-mystifying what happened at the capillary level, I had other outcomes to cover! At the time, I knew I needed to do something different, I just had absolutely no idea what that was going to be. Years later, after working with schools across British Columbia, the US and Asia, I have come to realize that I was not alone in having this ‘nemesis outcome’ in my Biology course: every course has outcomes where we know kids are going to struggle. And even though many of our schools in our District currently have “PLC time” where teachers collaborate on strategies to improve student learning, and that I used to be the Principal of one of the only “model PLC schools” at the time in British Columbia--we still have these same outcomes where students struggle, even though we know exactly which ones they are and ‘collaborate’ about them each week! We all know that having “PLC time” or being a “learning community” has never been enough--many of our schools would say that their PLC time isn’t as focused as it could be on student and teacher learning. In fact, some of our teachers might go so far as to say their PLCs are impinging on valuable instructional time. And after reading the Gates Foundation Report on teachers perceptions of current models of professional development and collaboration in schools, I know our educators are not alone in their thinking about what is and is not working for improving student achievement. What we knew for sure is that we wanted and needed to do something different. Last May in our school district, I asked teachers and administrators at five of our schools to try Learning Sprints in an attempt to take a new approach to those outcomes where we knew certain students struggled the most. We chose to investigate Sprints for a few reasons:

I purposefully chose the month of May to test another important aspect of Sprints--that they were do-able, even for the busiest teacher. As we know, the lead up to summer holidays for teachers is a crazy time. Year-end field trips, track meets, science fairs and math expositions turn the May calendar into a nearly blacked out Bingo card. But one other thing is common for teachers nearing the end of the school year: to a person they are working hard to get those students who have struggled with certain outcomes across the finish line before the doors close for summer break. Yet as busy as our May was here in BC, after I sent out Simon’s introductory Sprints video to the five schools, teacher teams from five schools took the plunge into Sprints. In order to launch Learning Sprints in our district, we tried a number of things things to ensure that our educators had a positive learning experience that met their needs. And while every district will have their own approach, these were a few things we found to be successful. We...

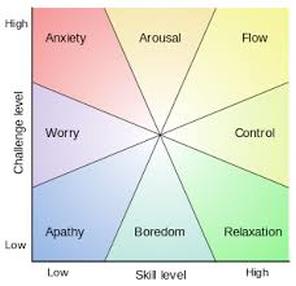

We also had a one-day workshop for administrators and teachers with Dr. Simon Breakspear a few months in advance. This was fortuitous and quite by chance--Simon happened to be working a short distance from our District, and we asked if he could pop over and spend a day with us. We wanted to give our educators a sense of the work of Agile Schools as well as a chance to ask any questions they might have. This visit was an added bonus: while the online tools are both user-friendly and robust, when we have the chance to have an expert work with us, well...we jumped at it. And so the five teams came to Day One, and we worked through the foundations of Sprints. In each of the Define, Understand, and Design phases, we used the short video to describe each section, and at least one of the suggested tools to help guide participants through learning the work of Sprints by doing the work of Sprints. Each of the groups found these tools to be valuable, but they also found the Sprints Canvas to be essential for ensuring that the great discussions that were taking place were being transformed to actions for their classrooms that they could take away at the end of our first session. Each of the teams successfully planned their Sprint. They got ‘granular’ and targeted a specific learning outcome and the smallest group of students that they could in their classes. They determined the current learning experience for their students and the types of instructional strategies they were attempting in their classes. They took advantage of the expertise of their colleagues in the room as well as external expertise through their research of promising strategies in their targeted outcome area. They determined the lean evidence they would be collecting during their Sprint, and finally, they presented their plan to a team from a different school to get warm feedback, cool feedback and suggestions in the true spirit of “hard on the content, soft on the people”. Our educators left Day One excited and energized, knowing that we would be reconnecting as a group in just four short weeks. They also left feeling supported: each of the Principals who attended were tasked with checking in with each of the teams in addition to their Sprint meetings to ensure teachers had what they needed to execute their Sprint. Our teams returned to us four weeks later. As a facilitator I was curious to see how our educators were feeling after such a short period of time and what kind of progress: maybe they didn’t call their target outcome a ‘nemesis outcome’ like I did, but they were working on an outcome that was important to them and their students! What did they find? What were the changes they saw in student learning? Were there any changes? What worked? What didn’t? What’s next? I had a lot of questions. And wow, did we hear a lot of answers. To begin the second session, we had participants do a reflection protocol. Team members from different Sprint teams interviewed each other and then reconnected with their school team to debrief about what they heard and what modifications they might make to future Sprints they were going to do at their schools. One of the major themes that came out from the group was around evidence collection: nearly every team mentioned that they needed to be even ‘leaner’ in how they collected evidence of learning in the target outcome area. They recognized that there were so many quick and easy ways that they could have collected evidence of learning from students that are not ‘formal’ but still inform teachers about strategies that are working and not working for lifting student outcomes. Another major theme was that their Sprint made a difference to student learning AND to their instruction. The evidence that they collected showed tangible changes in student learning. Period. As we shared around the room, some notable things our educators said included: "Sprints allowed us to find what the actual problem was, not what we thought it was." "After doing Sprints, I realize that we tend to just re-teach, rather than address skill gaps or identify missing sub-skills" "Sprints gave me the opportunity to gain insight into the learning styles of individual students." "We should do more quick, easy assessments for learning, rather than making assumptions about what students know." And in a “Before I thought, now I think protocol” to end Day 2, two important points were made that resonated throughout the group: "Before Sprints I used to think it would be impossible to see the impact of small changes to my practice...now I think I can tune my instruction over time to increase its efficacy " "Before Sprints, I used to think 'How can I fit ONE MORE THING'?", now I think "I HAVE to do this!" for my students." From a facilitator’s perspective, I was shocked at the energy of the group at the end of their first Sprint, and when I asked them if there was one thing that surprised them about Sprints that they would tell their colleagues, as a collective the group said “Sprints are easy to do and they make a difference”. And to a person, each team member said they will be doing Sprints again. But one of the most poignant comments was made a few days after the completion of Day 2. The Principal of one of our pilot schools informed me that his two teachers were starting another Learning Sprint for the last three weeks of the school year, and said this: “Learning Sprints is a game-changer for our collaboration time. It is the missing link.” I couldn’t agree more. Going forward, Learning Sprints will be a vital piece of collaboration, design, reflection and iteration in our professional learning cycle for our school district. Having our teachers work together as high-functioning teams with a tight focus to provide us with rapid information on that improves student and educator achievement is something we can absolutely get behind. As a result of our Learning Sprints pilot we are ramping up our Sprints efforts here in Kamloops (starting again in three weeks) to take our PLCs and collaborative time to another level. If you are looking to bring meaning and results to your teacher collaboration, I believe that Learning Sprints will make a difference. But don’t believe me! Follow this link to watch the short video and hear what our teachers had to say. I think you will be surprised! As a school Principal, I remember feeling like the night before Day One was not dissimilar to New Year’s Eve. I would always be filled with resolutions about how I was going to make the first day, first week, and first month special for our learners--our students, teachers, and parents. Two weeks prior to school before anyone came back, I would begin to plan that first day experience for the kids, the opening staff meeting activities for the staff, and picture how I was going to make parents (both new and returning) feel special at our school. My whiteboard would be filled with ideas, I would be checking YouTube for the funniest and most inspirational videos, and I would be scouring Twitter to see the cool ideas that others in my PLN were going to try in their schools and districts around the world. And while I had the best of intentions about that first day of school, each year I was making the same notable mistake.

I wasn’t using the people who were going to experience Day One in our school to design Day One in our school. Day One is an experience. We all remember it, don’t we? As students we all remember running to the front door of the school to see “The List”--the long sheets of paper that told us which teacher we were going to have, and who was going to be in our class. We looked forward to reconnecting with friends and reminiscing about barbecues, camping trips, and the occasional summer job mishap that made us a little happier to be coming back to our classes. And as educators, while we might not want to admit it, we still didn’t sleep all that well night before the first day of school: even as the most seasoned of veterans, we couldn’t help but feel a few jitters just like we did when we first started teaching. Day One can be a special time. So how could we make a Day One experience that surprises our students? One that has our parents raving in the coffee shops and on the sidelines of the soccer fields? And one that inspires our teachers to feel that same excitement on Day Two, Day Three, and even Day 180? #1 - Appreciate the Current Learner Experience As school leaders, we have our experiences with Day One,but what does that first day feel like for a new student or new parent? One thing that school leaders can do is reach out to students and parents who went through the experience in the last year or two and ask a basic question: “What was the first day of school like for you?” How about the opening staff meeting? School leaders often design this on their own, yet why not get a team of staff members together to ask them this same question? Doing our educational ethnography is key--we need to listen, and to find those ‘pain points’ that people might have so that we can turn them into opportunities. It is also vital to get multiple and varied perspectives: we can’t just ask those staff members who we might like, or who are our “go-to” staff members, we need to get an authentic cross-section of perspectives (Yes, that means listening to people you might not normally ask!) At a conference a couple of years ago, a colleague said something that has resonated with me to this day--”If you want to know the experience that people are having at your schools, why don’t you ask THEM?”. Seems simple, yet it is something that we often overlook. #2 - Co-create an illustration of the ideal Learning Experience (LX). A quick off-ramp that we can take as leaders is to get a whole host of perspectives and information through our ethnography and then run back to our office and try to make learning experiences all by ourselves. Designing the LX is a team sport! When you have all of that valuable ‘Day One Dirt’, bring it to a small team of ‘experts’ (that would be students, teachers, and or parents), and work together to create the vision! As a basic question like “What are the things we’ve experienced in the past that continue to inspire us today? and then...listen! Ask people to talk about lasting inspirational experiences that they have had, and not just in schools! Each of us has had an experience that has deeply impacted us, and inspired us to action. What were the elements that inspired us? Which of those elements could we borrow from outside of education that we could bring back INTO education? And as a result, what would we want people to be saying or producing during this experience? These pieces help us form our criteria for success. #3 - Come up with dozens of ideas that bring your illustration the LX to life. Remember, this is not just YOU coming up with ideas. I’m just going to say it, you haven’t cornered the market on good ideas: no matter how creative you might be, you alone are no match for a group of people who had already HAD the experience, and are GOING TO EXPERIENCE the LX. Get it? Ask the team a question like “How might we create a kick-off activity that inspires us and we are talking about for the whole year?” and see what people come up with. Volume is key here--don’t stop at what seems like a great idea, go for dozens of ideas, even hundreds of ideas! The first good idea is rarely the best idea. When your group is slowing down, you are entering fertile ground; this is where the craziest thoughts tend to come to the surface, the ones you think are not possible (but are VERY possible). When people are starting to giggle from ‘absurd idea’-fatigue, you are getting close. #4 - Test the best Now that you’ve got a few ideas that have some potential to inspire the whole year through, it’s tempting to just pick one and go with it. Don’t do it. As Saul Kaplan from the Business Innovation Factor says “Get off the whiteboard and get into the real world!”. It’s time to grab some of your ideas and have OTHERS take them for a test drive! Do they work? What needs tweaking? What do we need more of? What do we need to let go of? We must get feedback we get from ACTUAL consumers of the Learning Experience--not from the people in our design team. Our design team should be seen as conduits to others--have parents take the idea to other parents, kids to try it with other kids, and staff members to go to even the most reluctant of our colleagues to find out what they think. They will get the real dirt for you! If it doesn’t work with others, don’t stop--ask, “What could make this better!”. As Ronald Heifetz reminds us, in adaptive leadership we cannot see things as “immovable stakes in the ground”, but rather as experiments where we seek to learn more about what is working and what is not. Our measuring stick for success is how close we get to the criteria we created when we co-created our vision for an inspiring experience. #5 - Get it out there Once you have battle-tested the pieces of your Day One experience, it’s time to put them together and execute! At this point, you know you have hit the mark if your B to E ratio is high--your “barf to excitement ratio”! You know those butterflies that you get before you do something that is really exciting? If you and your team have those feelings, it is because you care a great deal about those who are going to have this experience--that’s exactly what you should be doing! But because you have worked with a team of learners right from the start and have involved other learners the whole way through, enjoy the moment. We often choose to celebrate the completion of the project, but remember, it’s not just about the end product. Firstly, our success is in the experience that others have, not in ‘finishing the job’. While you and your team have done a great deal of work, the Learner-Experience is KEY! You should be constantly collecting feedback to make the best even better. But right alongside of the experience you and the team have created for Day One is the experience you and your team have HAD. We create relationships through the time we spend and the things we do with each other--we develop our collective efficacy through doing things that are important and that make a difference to the learners in our schools. (Hattie says that’s pretty important, I hear). I know, I know. This sounds like it might take a lot of time. But think about those experiences in your life that have made a difference to you, that have TRULY inspired you to do something different. Were they worth it for you? And imagine that you can co-create a Day One experience for your students, your parents, and your teachers that is truly memorable, and develop collective efficacy at the same time. Does that sound like leadership? This year, design the Day One experience WITH your learners. I think you will be surprised by where it takes you and your school. Think different. Apple coined this phrase as a part of their advertising campaign back in 1997, and it has withstood the test of time. In fact, if you watch presentations of ‘innovative’ speakers in the world of K-12 education, I would bet that “Think different”, “Think outside of the box”, or something about adopting some sort of new and fantastic mindset would adorn at least three or four of their slides in their slide deck. Sigh. We all know different thinkers. We all know many people that think outside of the box. And with all of the outstanding work that Carol Dweck has done for us around the idea of growth mindset, I don’t think I have met a school leader that would tell you that they have anything BUT a growth mindset. (Imagine getting asked the question ”Do you have a growth mindset or a fixed mindset?”...how would you respond? If you aren’t sure, go ask ten school leader that question and see what they say.) In Learner Centered Design, LCD leaders don’t “think different”, or “think outside of the box”, and they certainly don’t need to have to have a superhuman mindset. LCD leaders DO different. They look outside of the box and then DO amazing things INSIDE of the box--they take the cards that they have been dealt and even if they have to bluff, they fake it ‘til they make it. And they take the “we can do this” attitude and translate it into action. They just get after it. Becky Kanis Margiotta is one of those people who just gets after it. Earlier this year at the Deeper Learning Conference in San Diego, I had the good fortune to listen to Becky (the co-founder of The Billions Institute) tell the story of how her and friend Joe McCannon were able to rapidly enact solutions to some of the world’s toughest challenges to those who could benefit most. Becky led the 100,000 Homes Campaign for Community Solutions, a nationwide large-scale change effort to find and house 100,000 of the most long-term and medically vulnerable homeless people in America by July 2014. If you were not there to listen to Becky speak, I can tell you that in her remarkable work, Becky didn’t have a lot of time for thoughts or ideas: Becky was all about action. Not only was she about getting things done, she was about undoing things that got in the way of getting those things done. And If you were there, you will agree with me when I say that her term for those who might have dropped the ball on the ‘action’ piece was truly unforgettable. Thinking is one thing. Doing is something quite different. Learner Centered Design IS doing different. It's working closely with those who are having a problem in our schools and solving the problem with them, as opposed to working with an inner circle to solve a problem FOR them and wondering afterward why those affected weren't happy with the result. It's spending the time to listen rather than solve. It's about knowing that the first idea is not the best idea, and that any idea is only as good as the feedback that we get from those who will have to live with the idea. It's about celebrating the feedback we get from our learners on the Learning Experience and the connections we develop through the process of creating this experience rather than clapping ourselves on the back for the solution that we have come up with. It's about proliferating solutions through creating immersive experiences rather than telling people what we have done and what they should do. Do different. Saul Kaplan from the Business Innovation Factory captures it best: “Get off the whiteboard and get into the real world”, he says with vigour to the audience each year at the BIF Summit every year in Providence, RI. In the final analysis, thoughts, ideas, and mindsets might be important, and even inspirational. However, LCD leaders know that these things mean little unless they translate into something tangible that students, parents, or educators can actually experience and feedback on so we can get to a solution that can actually make a difference to the Learner Experience (LX). So let’s not think different. Let’s DO different for our learners.  "We don't feel very appreciated." As a leader, how many times have you heard something like this, either directed at a leader by your colleagues, or even directed at you by people who work in your organization? In my own experiences in leading in schools or in the district office, I heard (and continue to hear) this more than I would like to admit. And when I reflect on those times when individuals or groups in my organization would say that they felt unappreciated, I realize that many of my responses to them really missed the mark. I have a core belief that people come to work each day wanting to do a good job. While there might be many that disagree with me, I have a hard time believing that the everyday person wakes up in the morning, rolls out of bed and says "Yep, today I am really going to blow it!" Whether it is in my world of K-12 education, or in health care, industry or business, while each of us has better days than others--days where we are more productive and have boundless energy to get the job done--I think we want to feel at the end of the day that we have worked hard and been effective in whatever field we are in. But the day-to-day grind can get to even the most positive of those among us! And while cynics might say "I can think of <enter your salary amount here> ways that you get appreciated for what you do", in the end it needs to be about more than money. It also needs to more than than how I used to respond as a leader, and how I see too many leaders express their appreciation for the work done by the people in their organization. In the past when I heard that people weren't feeling valued in my schools, I thought that the best way to show my gratitude would be to bring people together, to congratulate them, and to tell them how proud I was of the work that they were doing. I might buy lunch for everyone, or staff clothing. Every once in a while, I might have an evening barbecue on a Friday with food and beer for everyone. And while I might have engendered some cheer and good spirits (pun intended), I noticed that any positive effects were short-term. Yet this makes sense, doesn't it? Imagine that you were working really hard, but you were frustrated with certain aspects of your job, perhaps aspects you thought should be changed. That COULD be changed, just with a few tweaks if someone would take the time to ask you. But imagine that in response to your frustration, someone handed you a platter of cured meats and a beer at a party and told you "Thanks for all of your work." Does that make the frustration go away? #nope While I want to say that I was alone in this 'cake and beer' approach, too often I see leaders doing exactly what I did: they view 'appreciation' in terms of recognition and celebration. Make no mistake, most of us love a public compliment or some nice appetizers and a free pint at a party. But once the applause ceases and the lights go down at the end of the evening, a short sleep later it's back to business as usual. And very frequently when we get back into the routine of an average day, staring at the piles of marking, paperwork, or minutia of the moment, it's right back to feeling unappreciated. Cake and compliments don't change a thing. In Changing Change Using Learner-Centered Design, the goal of appreciation is not to recognize accomplishments. When leaders of Learner-Centered Design begin the Appreciate phase, they must do something that is far more meaningful than any cake or party--they need to LISTEN to the people that they are serving as leaders. The goal of Appreciate is to develop the most in-depth and fulsome understanding of the given experience that our people are having--whether it is understanding the student experience in our classrooms, the educator experiences in our meetings, or the parent experience with our websites or parent-teacher interviews, it is the mandate of the LCD Leader and their team to become the cameraman rather than the commentator on the experience by listening without judgement and seeking to understand rather than solve. They need to be educational ethnographers that use all means necessary to understand the current state of affairs, and then use those understandings to illustrate a vision of the ideal, brainstorm and test ideas, and then proliferate the changes that make a difference. In K-12 education, the number one factor influencing student achievement is "collective teacher efficacy" - the idea that a staff’s shared belief that through their collective action, they can positively influence student outcomes for all students. When we have teachers with high efficacy, they show greater willingness to try new things with students and set more challenging goals. Giving people cake and compliments does not change their belief that they make a difference. However, when leaders APPRECIATE the current challenges had by those in their schools, districts, and other fields and industries, and then use those observations to change that experience through the Learner-Centered Design model, they truly demonstrate to those who work in their organizations that their voice and their actions make a difference. Sounds a lot like efficacy to me. To learn more about Learner-Centered Design, visit http://www.pblconsulting.org/  Professional Learning Communities. Response To Intervention. Instructional Rounds. Flipped Learning. BYOD. PBIS. PBL. AFL. 1:1. Sigh. Have you ever taken five minutes to jot down the initiatives that you have going in your school or district? Or the ones that you have had going at some point in the past? Or even those programs that, if you squinted, you might still see remnants of them--you know, the ones that no one can quite determine when they started or ended--they just seemed to fade into the background, much like the once-splashy posters on our Counselling Office billboards or the rotating messages on our electronic signs. If you are anything like me, you likely find it difficult to recall and much harder to reconcile the amount of time and money each of us has spent chasing after the next 'holy grail'-like program that came our way when we know that the resources required to make them successful are so woefully scarce in supply. Earlier this year, as a member of the Agile Schools Faculty, I had the chance to work along side Dr. Simon Breakspear at the summer Educational Leadership Academy (#ataleads16) put on by Jeff Johnson and the Alberta Teachers' Association in Edmonton. It was both inspiring and challenging to take a deep dive into designing research-based, high-impact projects with classroom, school and district leaders for five intense, immersive and practical days. During one of the early sessions, Simon asked each of the participants to do a "stock-take" (on this side of the Pacific, we would say "inventory") of the initiatives they had done or were currently doing in their schools. Many generated lists similar to the one above, and even more created ones that were much longer. But then Simon asked the group to examine their lists to determine which ones they felt were actually making a tangible difference to student learning in the classroom. After a number of people began ruefully shaking their heads, Simon said something that truly resonated with the entire group (including me): But here's the thing: no one was saying that it was 'wrong' for schools and districts to look for promising new approaches to improving classroom practice, nor was anyone saying it was 'wrong' to attempt organize our time, efforts and resources around practices that are research-based and genuinely improve classroom practice and student learning. But before we jump headlong into 'the next big thing', we need to have a laser-like focus on the actual impact that the initiative has on student learning and the type of learning that educators will need in order to help them effectively implement the initiative in a way that makes a visible difference at the classroom level. As we know, the goal of an educational initiative is not to be 'doing' a program, it is to improve teaching and learning. Does it matter if we have become a professional learning community if we don't see a change to teaching and learning in our classrooms? Does it matter if we "do" Instructional Rounds in our schools if we continuously have the same problem of practice? Nope. Not a bit. In preparation for the Education Leadership Academy, Simon and I spent a great deal of time pushing each other about the composite pieces that we felt were important for teacher learning. Simon spoke from his experiences as a teacher and as a researcher in seeing and working with dozens of educational jurisdictions around the globe, who use a multitude of methods to engage teachers in professional learning. I came at it from the point of view of a Principal who has attempted to implement the approaches listed in the "stock-take" at the beginning of this post with subsequent results that ranged from moderate success to complete and abject failure. In the end, our thinking led us to a lens through which school leaders could look critically at their own "stock-take" of initiatives to determine whether those ideas had real potential to have a deep and lasting impact on the learning in their classrooms and with their educators. We can determine whether the initiative can crack the C.O.D.E of teacher learning. If the initiative, approach, or professional development is Connected, Observable, Developmental, and Embedded for teachers, it can significantly impact teaching and learning at the classroom level. CONNECTED...to the classroom, learning, and to each other Do you enjoy being electrocuted? Being immersed in water so cold that the ice in it doesn't melt? Having your clothes and skin torn by barbed wire? Sounds like a barrel of monkeys, doesn't it? So why do thousands of people around the globe voluntarily do these things to themselves in events like the Tough Mudder? Doing something challenging with a group of like-minded people connects us to the task, but more importantly, it connects us to each other. Learning is social, and while learning about new approaches to teaching and learning is not the same as being immersed in an ice bath, changing classroom practices can represent a significant shock to the system. As a result, it is vital that the learning experiences that come from initiatives or pro-d connect our teachers to one another: we must create a supportive, encouraging, and laterally accountable environment (much like a Tough Mudder team) to deal with obstacles that they will encounter along the way. Earlier this year, I sat across from Dylan Wiliam at dinner after learning from him earlier in the day at a conference session. He looked at me and said something that has resonated with me ever since. He said "I don't know why Principals would spend one second trying to implement something that isn't proven by research to improve learning." If there is no research to connect the initiative to improvement in student learning, he said, schools and districts don't have the money or time to waste on it. Period. I listened. I learned. While we all have ideas about what we think 'works' and 'doesn't work' in classrooms, if there is no foundation of research to the initiative we are considering, Dylan is right, we don't have the time to bother. Dr. Richard Elmore of the Harvard Graduate School of Education describes the importance of professional development being directly connected to the classroom. In one of his "laws" of professional development, he says "the impact of professional development is inverse to the square of its distance from the classroom". Professional development that requires educators to really chew on meaty instructional issues with each other and grapple with approaches in their own setting is professional development that is worth doing. Inasmuch as there can be value to offsite professional development, the more connected that educators are to their own classroom situation when they are learning, the higher the likelihood that the initiative will make a visible difference in their own classroom. OBSERVABLE...to all of us, BY all of us The products of any professional development that we do should be readily and plainly observable. When facilitating Instructional Rounds in schools, I ask educators to focus on what students are saying, doing, writing, and producing as a result of the tasks they have been assigned and the instruction they have been given. But how often do we consider what our educators saying, doing, writing and producing at an inservice or conference that they are attending? If educators are sitting passively in a large conference listening to a witty and charming 'edutainer' show pictures and YouTube clips while telling amusing anecdotes, what is the evidence that our educators have learned a single thing? The age-old proclamation of "If you get one good thing out of a conference, it was a good conference" doesn't fly anymore: with shrinking PD budgets and more demands on our time, the educational return on a $2000 investment needs to be better than that. WAY better. When we are considering any initiative, we should be able to clearly articulate what an observer would see in our classrooms as a result. But who is observing? One of the saddest revelations that I had as a Principal happened when I was doing teacher observations. Not because of what I was observing in the classroom, but because I was the only one who was doing the observing! Far too often, the people who are doing the bulk of teacher observations are not teachers--this is wrong. More of our professional development needs to be directly connected to the classroom, with teachers observing and working with other teachers. And if we are to use the excuse that there isn't enough money, consider that $2000 conference bill to send one teacher to a conference to get "one good thing", as we have all done far too often in the past. That same $2000 is the cost of five or six release days--or 10 or 12 half days. How much could be done by releasing four teachers for three half days to observe and work with other teachers? DEVELOPMENTAL...it meets us where we are at Would we ask a new swimmer to jump off of the high diving board? A novice skier to head down a double-black diamond run? Or would we tell someone that the only car they should buy is a new Mercedes Benz when we know they only have a $10000 budget? While each of these scenarios seems absurd, imagine what it feels like for an educator to be asked to "do Project-Based Learning" in their classes, or to "welcome observers into their classroom" when they are used to being left on their own behind a closed classroom door to teach the way that they have found to be successful for themselves and their students. While there may be a research-base to an educational initiative that supports a positive change in classroom practice, research does not automatically open classroom doors: having a colleague or a team come to observe their classroom can truly be a 'double-black diamond' moment for many educators. And rightfully so! In most cases, we have not taken them down a 'green run' with ideas like PBL or classroom observation. Educational initiatives and professional development must provide multiple entry points for our educators, and provide the appropriate level of challenge at each level. In his book "Flow: The Psychology of Optimal Experience", Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi (pronounced "mee-hi, cheek-sent-me-hi" if you're curious) talks about the importance of "flow" when we are considering whether the activities we design allow participants to get into "the zone". However, we must not only acknowledge the challenge level of the activity, we have to ensure a certain skill level of our educators so we help them move from a state of anxiety or boredom to a place where they are optimally engaged. With something like classroom observation, we might create multiple entry points for our educators like this: